MIAF: Pichet Klunchun and Myself

Festival diary #7

TN is recovering nicely after three weeks of extreme culture vulturing (not as extreme on my part as some others, to whom I can only tip my hat in astonishment) and might soon be able to receive visitors. It's been an intense, fascinating, diverse and very enjoyable time. I guess everyone cuts a festival like this their own way, and will have their own story on it: but me, I feel well fed.

What I will probably remember most from MIAF 2006 is Romeo Castelluci's Tragedia Endogonidia and the piece I talk about below. Perhaps what both of them have in common is the courage to do only what they needed to, and nothing more. Which is much harder than it sounds.

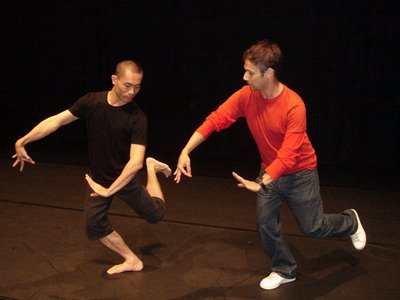

Pichet Klunchun and Myself, concept by Jérôme Bel, by and with Jérôme Bel and Pichet Klunchun. Playhouse, Victorian Arts Centre

After the rich diet of the past three weeks, this startling and beautiful piece comes as a cleansing of the palate: light, dry, subtle, leaving a profound aftertaste. Plichet Klunchun and Myself is an often very funny encounter between two very different artists, the controversial contemporary French choreographer Jérôme Bel and the traditional Thai dancer Pichet Klunchun. Or, more strictly speaking, a performance of an encounter. Perhaps what is most astonishing about this show is that it feels like a first meeting, although, as audience members, we know perfectly well that this is a piece that has been performed many times.

It is about as simple as it gets. Two chairs are placed facing each other on the vast emptiness of the stripped Playhouse stage. On one sits Jérôme Bel, who looks as if he has recently fallen out of bed, dressed in white sneakers, a casual pullover and jeans. On the other sits Pichet Klunchun, dressed in long black shorts and a black t-shirt. Bel has an ibook open on his lap, from which he reads a series of prepared questions for Klunchun.

The questions begin as simply as the staging: what is your name? What is your profession? Why are you a dancer? The answers, as might be expected, are not so simple: the third elicits a long answer about how his mother had longed for a son, and had made an offering at a Buddhist temple, after which she had become pregnant with Pichet. In the face of Bel's bafflement at what this has to do with dance, he explains that the temple god appreciated dance, and so after his birth, his mother commissioned a performance before the temple statue. It seems, although he does not say so, that he was destined for his vocation.

Klunchun is a Khon dancer, a very stylised form of traditional Thai dance, and soon Bel wants to see what it is. What follows is about as lucid an explanation, complete with demonstrations, of the physical language of Khon and the formal conventions of Asian theatre as you are likely to hear. He explains how the text relates to the movements, how the orchestra is on stage, and that the dance is masked, which means that the dancers themselves do not sing or speak.

Bel asks how Khon represents death on stage, and is shown various means of indirect representation, since it is bad luck to represent a death. In one, the warrior dies off-stage; in another, the grieving family and retainers and possibly the deceased's army walk very slowly across the stage (a scene which can apparently take 20 minutes). The last, in which a courtly lady is told of the death of her husband, wiping away her tears so that no one will see her grief, is exquisitely beautiful, and Bel is visibly moved by it.

Soon it is Klunchun's turn, and he asks Bel the same questions: who he is, what he does, and why he does it. This time it is Klunchun's turn to be baffled. Bel is one of the foremost practitioners of contemporary European dance. His performances have caused people to throw objects at the dancers or demand their money back (apparently, they don't get it). When Bel demonstrates his favourite dance (which involves standing still on stage, doing nothing) Klunchun is dumbstruck. Why would anyone pay to see that? he asks.

Bel then explains why his choreography produces so little dance: he is reacting, he says, against the Society of the Spectacle. In a society in which people are alienated from real human relationship by the mediation of images, he refuses to entertain: he wants to disappoint his audience's expectations, in order to permit the possibility that something else, something more authentic, might occur. People go to see contemporary art, he explains, because they don't know what will happen, not because they do know. They go in the hope that they will see something that articulates the experiences they have in their daily lives.

Klunchun asks him how he represents death, and Bel puts on a recording of Roberta Flack's Killing Me Softly and does his standing thing again. Before long he drops to his knees, and finally he ends up lying on the floor. This elicits a moving story from Klunchun about the death of his mother, who was paralysed for 11 years before she died.

"I want to make space for people to have their own thoughts about death," says Bel, adding, almost as an afterthought, "Sometimes I make too much space..."

"I liked it, because it is traditional," answers Klunchun.

Bel becomes very still and is silent for a long time. He is clearly appalled. "I think you are wrong," he says finally.

"Maybe - maybe what I mean is that it is international," replies Klunchun. "Death is very international."

He recognises something, suggests Bel, just as Bel was able to understand the gesture of the woman wiping away the tears from her face, even though he couldn't understand, without explanation, the complex and subtle vocabulary of Khon dance. The movement in these dances expressed something that was humanly common across their very different cultures.

Just in case we get too comfortable about the universality of art, the dialogue ends with Bel enthusiastically beginning to take off his trousers to demonstrate his nude choreography. Klunchun is horrified and begs him to stop. "Don't you like my work?" asks Bel, hurt. "No, no, it's not that," says Klunchun. "I get it. It's just that I don't want to see you naked in front of me...we don't do that..."

There is much art behind the apparent artlessness of this show: it is in fact a brilliant example of the aesthetic Bel expresses. The convention of having a performer watch someone else on stage is, for example, extremely theatrical, and here it is consciously employed to elicit our complicity as an audience: we too are watching. Here are two very different artists from very different societies explaining their work and their lives to each other, and hence to us. Their curiosity, their occasional offence, their mutual amusement and respect, make this show a riveting and, finally, profound meditation on human communication.

I have seldom seen a work so absolutely lucid, or so luminous with humanity. And lest you still think that two dancers talking about their work for almost two hours sounds dull, I took along my personal boredom-meter, my 11-year-old son. He was enchanted: he clapped all the dances, laughed at the humour, and talked exhaustingly about the relationship between Thai dance and Thai architecture and Jérôme Bel's willingness to take off his trousers all the way home.

7 comments:

I ran into a 'fellow traveller' who -- like you, me and everyone else I know who has seen this show -- was bowled over by it, and he confirmed that there were significant differences from show to show. If not in structure, then certainly in execution and answer.

Even from the scenes you describe, I can pick a few. Did Bel lip synch the lyrics to Killing Me Softly? (He did on Friday night!)

The fact, too, that the show was 15-20 minutes longer than advertised was another clue that they keep it knife-edge fresh.

Yes, Bel did the lip synching. I wonder what I would think of his dance (or non-dance) pieces? I'm kin of itching to see them now.

I'm not surprised to hear that they improvise it; that sense of freshness is palpable. Brave work.

It's bad enough that there are more things in New York than I can see. But now I'm beginning to wish I could go to Melbourne for the next MIAF. There will be another one, won't there?

After reading the utterly dispiriting pages in the Age "wrapping up" the festival it was such a relief to read your pelucid review of this inspiriting performance, Alison. I can't remember when I last thought and felt so much and at the same time in the theatre - though the Castelluci came close.

Thanks Meredith. And hey John, come to Melbourne - the world's "most liveable city"! - as the tourist people keep telling us. MIAF is on every year, and Kristy Edmunds is responsible for at least one more (and possibly another).

Great show. . At delhi

So it is! Glad to see it's still touring!

Post a Comment