MIAF: Voyage

Festival diary #4

Voyage by dumb type, performed by Manna Fujiwara, Yuko Hirai, Takao Kawaguchi, Hidekaazu Maeda, Seiko Ouchi, So Ozaki, Noriko Sunayama, Mayumi Tanaka, Misako Yabuuchi. Visuals by Shiro Takatani, Takayuki Fujimoto, Hiromasa Tomari. Playhouse, Victorian Arts Centre

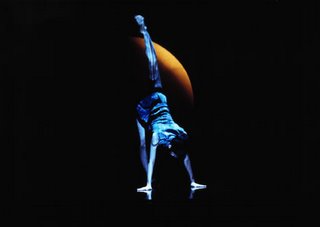

Darkness. After a time, the faintest of illuminations; at first you are not certain whether it is a trick of the eyes. An electronic roar that sounds disconcertingly at once like an amplified organic sound – perhaps the rushing of blood through the body – and machine-like begins to swell up from silence. As your eyes adjust and the lights slowly brighten, you begin to make out the edges of three huge silver spheres on stage, and a human form moving in the shadows against the wall of electronic sound. The dancer’s movements are like flight, like swimming; her body is reflected in the polished floor beneath her. She returns to darkness. The first movement of Voyage, dumb type’s hypnotically beautifully multimedia show, is at once spectacular – the beauty of the unadorned human body against the austere simplicity of the spheres is striking – and subtle. It introduces a series of autonomous vignettes that invoke a myriad of responses, but which all highlight the fragility of the human body in a world which is at once beautiful and threatening.

The first movement of Voyage, dumb type’s hypnotically beautifully multimedia show, is at once spectacular – the beauty of the unadorned human body against the austere simplicity of the spheres is striking – and subtle. It introduces a series of autonomous vignettes that invoke a myriad of responses, but which all highlight the fragility of the human body in a world which is at once beautiful and threatening.

dumb type is that rare beast, a collective: as they put it, “we don’t want a king”. Formed in Kyoto in the 1980s by a bunch of arts students frustrated by the narrowness of their studies, the company brought together artists from a variety of backgrounds who began to pioneer multimedia theatre in Japan. Clearly inspired by Pina Bausch's conflation of dance and theatre, they create work of an intriguing beauty: it skirts the edges of kitsch, finding its expressiveness by magnifying and making symbolic what are sometimes very ordinary elements of contemporary life. Voyage is centrally a series of expressions of anxiety and yearning, through which run several common images and concerns. The transience and speed of contemporary life is placed in deliberate tension with qualities of reflectiveness and slowness. Most gestures in the choreography are simple and contemplative, aside from one jazzy piece, a kind of satire of airports, which features mini-skirted air hostesses doing a Broadway dance number. For the most part, the work focuses on stillness: a woman lies on a desk idly typing flight schedules on a typewriter - itself a relic of a vanished modernity - interspersed with with questions: where am I? where are you? Her image is reflected in a giant projection, which closes in on the keys typing: finally it is typing cancelled flights. "Baghdad: cancelled."

Voyage is centrally a series of expressions of anxiety and yearning, through which run several common images and concerns. The transience and speed of contemporary life is placed in deliberate tension with qualities of reflectiveness and slowness. Most gestures in the choreography are simple and contemplative, aside from one jazzy piece, a kind of satire of airports, which features mini-skirted air hostesses doing a Broadway dance number. For the most part, the work focuses on stillness: a woman lies on a desk idly typing flight schedules on a typewriter - itself a relic of a vanished modernity - interspersed with with questions: where am I? where are you? Her image is reflected in a giant projection, which closes in on the keys typing: finally it is typing cancelled flights. "Baghdad: cancelled."

Text plays into these images in very interesting ways that make some of these sequences huge visual poems: in a scene where Misako and Mayumi run in the dark, lamps affixed to their foreheads, searching for each other, they cry out in Japanese while the text runs across the back of the stage in English. Surtitles, of course, but not merely surtitles, as they are also visual elements in their own right.

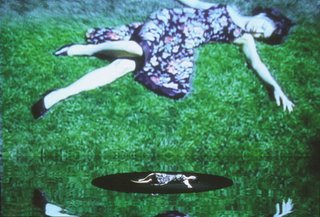

In another sequence, which begins with a huge lightbulb swinging like a luminous pendulum over the dark stage, projected words fall down from the ceiling, rippling over the performers’ bodies. They are all single words, starting with "slow", that conjure the transience of time: "before", "once", "moment". A particularly beautiful vignette features a voiceover that lists a long sequence of wishes, beginning with “I wish I were an angel”. A woman lies prone on a circular mat in the middle of the stage, surrounded by gorgeous images of the natural world which transform to a giant doubling of herself, projected on the back wall of the stage and reflected on the stage floor. The projected image, with its actual grass, dominates the physically present woman, a manifestation of the hyperrality of the virtual image. At first benign and fanciful, the vague banality of the wishes become more and more suggestive of human disaster, until the words dissolve into an earsplitting shriek of white noise, while the image becomes a matrix-like flow of digital numbers and letters, before resolving again into sense. But now the seemingly childlike "I wish I were an angel" is more sinister; it is a deathwish, an inability to cope with the pain of loss.

A particularly beautiful vignette features a voiceover that lists a long sequence of wishes, beginning with “I wish I were an angel”. A woman lies prone on a circular mat in the middle of the stage, surrounded by gorgeous images of the natural world which transform to a giant doubling of herself, projected on the back wall of the stage and reflected on the stage floor. The projected image, with its actual grass, dominates the physically present woman, a manifestation of the hyperrality of the virtual image. At first benign and fanciful, the vague banality of the wishes become more and more suggestive of human disaster, until the words dissolve into an earsplitting shriek of white noise, while the image becomes a matrix-like flow of digital numbers and letters, before resolving again into sense. But now the seemingly childlike "I wish I were an angel" is more sinister; it is a deathwish, an inability to cope with the pain of loss.

Voyage finishes with a dance which is a reflection of the opening scene, but where there had been blank spheres, now the solo performer moves against a changing background of flightmaps. It suggests that human restlessness is not so much about arrival as a marking, the traces we leave on our planet. The natural world is a major feature of this piece, but in a way that almost seems nostalgic: there are projected images of the sky or forests or mountains that are at once gorgeously lush and, in their very magnification and heightened colour, curiously alienated. They are are contrasted with images of with human mapping and exploration - airports, for example, or flight maps of the Middle East, in which no-go zones flash up the subliminal fears that underlie so much of this imagery.

The dichotomies between interior, private lives and public impersonal spaces, between the natural world and technology, or between private and public anxieties, give these theatrical images fruitful tensions and complexities: only once, during a dance that seemed to be in empty arctic space, did I find my absorption flagging. Ryoji Ikeda's brooding soundscape effectively uses ambient sound - the amplified dragging out of a plastic sheet that is part of the set, for example, or the sound of stones being shaken in a box - as well as electronic music. And the lighting is pure genius, a dance in itself.

Pictures: Voyage by dumb type. Photos: Kazuo Fukunaga