2007 has been a big year for Little Alison. After seven years hard labour, I finished my fantasy quartet, all 2000 pages of it. I also completed my next collection of poetry, called (with only a smidgeon of irony) Theatre, which is coming out with Salt Publishing next year. The blog's had a good year - in 2007, TN had around 165,000 unique visitors (almost quarter of a million hits), an average of about 20,000 a month, almost tripling the traffic from last year.

2007 has been a big year for Little Alison. After seven years hard labour, I finished my fantasy quartet, all 2000 pages of it. I also completed my next collection of poetry, called (with only a smidgeon of irony) Theatre, which is coming out with Salt Publishing next year. The blog's had a good year - in 2007, TN had around 165,000 unique visitors (almost quarter of a million hits), an average of about 20,000 a month, almost tripling the traffic from last year.I've gone full circle and ended up where I started, back in the hurly-burly of daily newspapers (where, as Stella Gibbons memorably remarked, one's style, like one's life, is nasty, brutish and short): I became Melbourne theatre reviewer for the Australian, and began doing the odd gig for the Guardian. And then Howard was voted out of government and I accidentally deleted four years of email. No wonder I'm tired.

In between all that, as a quick glance at a list of my reviews will reveal, I saw, and wrote about, almost 100 shows. Which seems like a lot to me, though battle-hardened veterans (I'm looking at you, Mr Boyd) might snort dismissively: a proper critic sees six shows a week, and tots up a total of something like 300. In my defence, I can only say that I've never pretended to be anything but an improper critic.

In between all that, as a quick glance at a list of my reviews will reveal, I saw, and wrote about, almost 100 shows. Which seems like a lot to me, though battle-hardened veterans (I'm looking at you, Mr Boyd) might snort dismissively: a proper critic sees six shows a week, and tots up a total of something like 300. In my defence, I can only say that I've never pretended to be anything but an improper critic.While I'm crunching the numbers - it's kind of fun and, in its own limited way, revealing - I count around 30 of those shows as things I wouldn't have missed for the world, making an excellence rating of about 30 per cent. That's pretty good going with something as volatile as theatre. This heads up to about 15 duds, shows that bravely challenged the trend of time's quickening and made it run like a river of porridge. This leaves around 55 per cent in the "good" category, shows I enjoyed without their blowing me away.

I've never been in a position to see everything on in Melbourne, and all through the year there have been shows I couldn't get to, and which - after hearing breathless reports from my extensive network of theatre spies - I'm sorry I ended up missing. But all the same, it's a fairly decent sampling. And it seems to me that, generally speaking, Melbourne theatre passes the medical with flying colours. The hue is rosy, the limbs are making lively gestures, the renaissance is on. There are those who like their culture dead, the chief zombie being Robin Usher of the Age, but me, I prefer to leave the theatre with my heart beating.

This liveliness has been driven by three major institutions - the Malthouse, the Melbourne International Arts Festival and the Victorian College of the Arts - with strong support from the independent theatre and dance scenes.

This liveliness has been driven by three major institutions - the Malthouse, the Melbourne International Arts Festival and the Victorian College of the Arts - with strong support from the independent theatre and dance scenes.The Malthouse has had a year of consolidation, with an eye turned to crowd-pleasers like Geoffrey Rush in Ionesco's Exit The King or Sleeping Beauty, and return seasons of successful shows from the independent theatre scene - The Pitch, from La Mama, The Eisteddfod, from the Store Room, or A Large Attendance in the Antechamber, from everywhere.

But it's also found space for experimental gems like Anna Tregloan's Black, the Bessie-winning dance/theatre piece Tense Dave, or the unruly anarchy of Uncle Semolina & Friends with OT. They put on a cabaret season, including the incomparable Paul Capsis, and they produced one of the Melbourne Festival's highlights, Barrie Kosky's The Tell-Tale Heart.

But it's also found space for experimental gems like Anna Tregloan's Black, the Bessie-winning dance/theatre piece Tense Dave, or the unruly anarchy of Uncle Semolina & Friends with OT. They put on a cabaret season, including the incomparable Paul Capsis, and they produced one of the Melbourne Festival's highlights, Barrie Kosky's The Tell-Tale Heart.I've enjoyed everything I've seen there this year - it's been various, stimulating, controversial and fun - and I can't say that about anywhere else. I'm not going to argue with any of those who are saying that the Malthouse is the most exciting theatre company in Australia.

And then there's the Melbourne Festival. Well, a lot of words have been spent on MIAF, so I'll just say that for this bright-eyed rabbit, this year's festival was, taken as a single event, the highlight of the year. Artistic director Kristy Edmunds delivered the goods bigtime: I spent 17 days buzzing around on a permanent high. If I lived in Singapore, I would have been arrested and sentenced to flogging. Aside from The Tell-Tale Heart, my highlights were Jérôme Bel’s The Show Must Go On, Dood Paard's Titus and Athol Fugard's Sizwe Banzi is Dead (though Laurie Anderson was pretty cool...)

And then there's the Melbourne Festival. Well, a lot of words have been spent on MIAF, so I'll just say that for this bright-eyed rabbit, this year's festival was, taken as a single event, the highlight of the year. Artistic director Kristy Edmunds delivered the goods bigtime: I spent 17 days buzzing around on a permanent high. If I lived in Singapore, I would have been arrested and sentenced to flogging. Aside from The Tell-Tale Heart, my highlights were Jérôme Bel’s The Show Must Go On, Dood Paard's Titus and Athol Fugard's Sizwe Banzi is Dead (though Laurie Anderson was pretty cool...) One of the peculiarities of Melbourne is that some of the best theatre here is made by students. The VCA sucks in talented youth, trains it within an inch of its life, and then gets the most interesting directors around town to throw it at fabulous texts. Ambition is the byword. The VCA production of Hélène Cixous's The Perjured City was one of this year's top shows. Their end-of-year productions of King Lear and A Dollhouse weren't far behind and I'm told that Yes, which regrettably I couldn't get to, was equally impressive.

One of the peculiarities of Melbourne is that some of the best theatre here is made by students. The VCA sucks in talented youth, trains it within an inch of its life, and then gets the most interesting directors around town to throw it at fabulous texts. Ambition is the byword. The VCA production of Hélène Cixous's The Perjured City was one of this year's top shows. Their end-of-year productions of King Lear and A Dollhouse weren't far behind and I'm told that Yes, which regrettably I couldn't get to, was equally impressive.This year dance indelibly entered my theatrical lexicon. It was, on the whole, a year to catch up - I saw several wonderful remounts. I've already mentioned Tense Dave, but there was also Lucy Guerin's Love Me and Aether, Chunky Move's Glow, and, courtesy of MIAF, a retrospective of Merce Cunningham. I might be learning something... Among the new work, last week's Brindabella from BalletLab was a knockout, and La Mama also hosted a memorable performance of Deborah Levy's B-File.

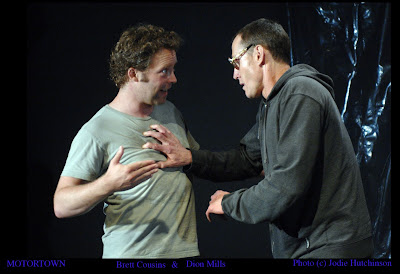

Outside the institutions, my top shows were Little Death's notable production of Philip Ridley's Mercury Fur, Simon Stone's wonderful adaptation of Wedekind's Spring Awakening and Ranters Theatre's gorgeous Holiday. Outside Melbourne, a tiny Adelaide company, Floogle, enterprisingly flew me over to see their production of Pinter's The Homecoming, which was as elegant a reading of that play as I am likely to see. There was Eleventh Hour's rivetingly erotic retelling of Othello. And - sacre bleu! - one of my theatre highlights was seen at the Melbourne International Film Festival - A Poor Theatre's The Tragedy of Hamlet: Prince of Denmark, which counts because I saw it first as a play and because it's part of the Malthouse's first season next year.

In fact, there was a lot of Shakespeare around in 2007, with a decidedly mixed hit rate. Bell Shakespeare made me eat my words by putting on a good production of Othello, but the much-anticipated RSC production of King Lear, with Sir Ian McKellen notoriously shedding his underpants, was one of this year's huge disappointments. I was forced to watch Peter Brook's film to remind myself that the play really is more than a comic opera.

In fact, there was a lot of Shakespeare around in 2007, with a decidedly mixed hit rate. Bell Shakespeare made me eat my words by putting on a good production of Othello, but the much-anticipated RSC production of King Lear, with Sir Ian McKellen notoriously shedding his underpants, was one of this year's huge disappointments. I was forced to watch Peter Brook's film to remind myself that the play really is more than a comic opera.So it wasn't all champagne and skittles. Which brings me to the Melbourne Theatre Company, currently looking like the ailing limb in an otherwise rather fit theatrical body.

To be fair, it wasn't all bad. Arthur Miller's All My Sons was a straight production of a classic that went like a train, although I admit that contrary reports from many reliable sources of the subsequent season made me wonder if the cast had reserved all their vim for opening night. I thought the MTC's production of Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? the most moving of the three I saw this year, and Thom Pain was a delightful surprise. I had a long argument with Alan Bennett's The History Boys, but I felt it was worth doing all the same.

The rest was a mixture of the forgettable, the competent and the plain awful. The MTC served up some of the worst nights I've spent in the theatre this year. It began the year ominously with the bafflingly bad production of Joe Orton's Entertaining Mr Sloane, and ended with what is my vote for worst show of the year, Jean Giraudoux's The Madwoman of Chaillot. Midyear there was the ineffably sentimental tedium of The Glass Soldier, one of the bottom five low-points of TN's theatrical year. It's notable that all three of these shows were directed by artistic director Simon Phillips.

The rest was a mixture of the forgettable, the competent and the plain awful. The MTC served up some of the worst nights I've spent in the theatre this year. It began the year ominously with the bafflingly bad production of Joe Orton's Entertaining Mr Sloane, and ended with what is my vote for worst show of the year, Jean Giraudoux's The Madwoman of Chaillot. Midyear there was the ineffably sentimental tedium of The Glass Soldier, one of the bottom five low-points of TN's theatrical year. It's notable that all three of these shows were directed by artistic director Simon Phillips.I guess Phillips has had a distracting year - not only is the MTC building a new theatre, but he's been out and about in the commercial world. But given the liveliness and invention of the theatre culture around it, our state company ought to be doing better. Much better. To go back to the dubious number crunching: if the dud percentage of theatre generally was 15 per cent, the MTC's individual dud percentage was around a third. And although several shows made my "good" category, not one blew me away.

Next year's program is, in prospect at least, similarly uninspired. But to finish on a positive note, next month the MTC is importing the STC's magnificent production of The Season at Sarsaparilla, so Melbourne will have a chance to see what happens when a state theatre company attempts to make theatre, instead of just putting on plays.

Next year's program is, in prospect at least, similarly uninspired. But to finish on a positive note, next month the MTC is importing the STC's magnificent production of The Season at Sarsaparilla, so Melbourne will have a chance to see what happens when a state theatre company attempts to make theatre, instead of just putting on plays.Well, that was my 2007. It was a vintage year, and it's brought me a great deal of pleasure. I want to thank all the theatre companies who kindly provided me with tickets, the many people who have encouraged me through the year, my blogger colleagues and, most of all, my readers and commenters (especially those who take issue with me). I've had a brilliant time, and I hope it's mutual.

TN is now taking some badly-needed time off, and will be back refreshed and - theoretically, at least - raring to go in the New Year. Me, I'm heading back to my poetic roots over the Yuletide break, and writing a new translation of Beowulf. (I don't know why, but sometimes one can't help these things). So a happy solstice to all of you, and I'll see you in 2008.

Pictures from top: Glow, by Chunky Move; Luke Mullins in Little Death's Mercury Fur; Geoffrey Rush and Julie Forsyth in Exit the King, Malthouse; Black by Anna Tregloan, Malthouse; Kagemi, Sankai Juku, Melbourne Festival; Ben Hjorth in the VCA's King Lear; Ian McKellen in the RSC's King Lear; Don's Party, MTC; The Season at Sarsaparilla, STC.