Motortown was written in four feverish days, at the time of the 2005 London bombings. British playwright Simon Stephens wanted to write, he says, a play “which inculpated more than it absolved. I wanted to write about my guilt in creating and perpetuating the culture that drove these wars…”

It’s the kind of impulse that can easily result in theatre that’s about as exciting as muesli. Thankfully, Motortown is too angry, too pitilessly honest and too sardonically funny to be earnest.

Motortown comes from a recognisable genre of plays that draw from George Büchner’s 18th century masterpiece Woyzeck, a play about an alienated returned soldier whose damaged psyche explodes in violence. As in David Mamet’s Edmond, the protagonist is in every scene, a kind of dystopic Everyman spiralling towards inevitable doom. He’s a symptom of a wider social sickness, a psychotic expression of a general moral vacuum that gnaws at the very heart of what it means to be human.

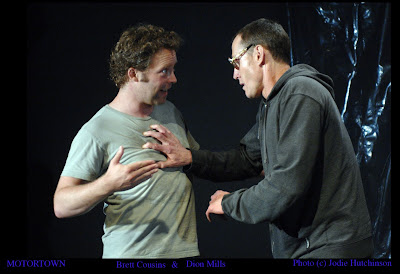

Danny (Brett Cousins) has bought himself out of the army after serving in Basra. Through his encounters with his ex-girlfriend, a petty arms dealer and some wealthy swingers, Stephens paints a scathing indictment of contemporary Britain. “The war was all right,” says Danny. “I miss it. It's just you come back to… this.”

These plays are also disturbing explorations of the crisis in masculinity that’s reflected, among other things, in a high suicide rate among men. Danny only admits how deeply scarred he is by his Basra experience in moments of crisis. This disconnection is linked to his compulsive lying; he seems incapable of telling the difference between fantasy and reality, and in part the play is driven by his different accounts of himself: a suggestion in one scene appears as a lie in the next.

In a particularly cruel scene, he is mocked by his ex-girlfriend Marley (Sarah Sutherland) for his impotence. His violence – like that of Woyzek or Edmond – is ultimately directed against women. But it's clear that Danny's problems predate his war experiences: the war only gives them horrifying expression.

As in Philip Ridley’s Mercury Fur, a recent hit in Sydney and Melbourne, the only real emotional connection occurs between brothers. Motortown begins and ends with Danny’s relationship with his disabled brother Lee (movingly protrayed by Dion Mills).

Laurence Strangio gives it a swift and powerful production, driven by a couple of excellent performances in the central roles of Danny and Lee. It’s not without flaws – some performances tend towards the mannered.

And Peter Mumford’s design – a floor painted in what I presume is crazy paving, with seatbelts suspended from the ceiling – is puzzling and distracting. But it’s a creditable production, and this spare, compelling play shines through with mordant clarity.

Picture: Brett Cousins (left) and Dion Mills in Motortown. Photo: Jodie Hutchinson

This review appeared in yesterday's Australian.

No comments:

Post a Comment