Friday, November 30, 2007

Ushering in some more canards

"Is (the festival)," thunders Usher, "supposed to be an exploration of cutting-edge contemporary works or a more rounded presentation of the best acts available from around the world and locally?" I'm not sure why these two things are mutually incompatible, but there we are. Anyway, which is enough to send a shiver down any aesthete's spine, Usher predictably regards new artistic director Brett Sheehy as a "safe and sure pair of hands". Though I ought to add that it's not fair to judge Sheehy through Usher's glasses.

In a startlingly mean-minded attack on the present artistic director Kristy Edmunds, Usher goes on to work the familiar canards - that the 2005 and 2006 festivals were no good (TN and many others thought 2005 was the most exciting for years), that Edmunds is underqualified and knows nothing about classical music, that the festival "ignores an affluent segment of Melbourne's culture lovers". He even - scandalously - hints that Edmunds is only interested in contemporary dance because her partner is dancer Ros Warby. And he carefully doesn't mention that MIAF 2007 was both a critical and sell-out success.

The problem with Usher's criticisms is that they have never borne much connection to things like actual programming, or even facts. Where he claims that Edmunds changed course in her tenure, I see a singular evolving vision. Where he claims that the festival was "elitist", I saw enthusiastic audiences across a very various demographic. During Edmunds' first festival, which nobody was said to attend, I was astounded by how many queues I hand to stand in to get into theatres.

As for those "fringey" acts; well, the fact that Usher hasn't heard of an artist doesn't mean that he or she isn't internationally famous. This is the senior arts reporter who didn't know that the Avignon Festival is the biggest theatre festival in Europe, and had to ask how to spell "Avignon".

He brings up John Truscott again as part of the festival's "tradition". The thing is, I agree with Usher that Truscott was a great festival director. It's just that I think Edmunds is in the same tradition. Like Edmunds, he strongly supported local artists and brought in the most exciting "cutting edge" work (I see Usher is at least avoiding the word "fringe") from around the world.

And Truscott - for all the holiness of his memory, now he's safely in the past - was beaten around the ears for it by the grinches, just as Edmunds is being beaten now.

Usher's solution to the dangerous art problem is that the State Government introduce "guidelines" to stop the festival being at the "whim" of every blow-in director. Aside from the absurdity of the suggestion - what does he mean? Thou Shalt Program Carmen Every Festival Or Else? - it's unbelievable that any arts commentator should be seriously calling for state-sanctioned art. Yes, there's a tradition here too - ever heard of Stalin?

UPDATE: Ming-Zhu swings in with the observation that it's all so old and stinky and that her peers complain that MIAF is too full of Grand Masters. "What do you hope to achieve?" asks the redoutable Ming. "Melbourne as a silent pocket of doddering biddies dwelling eternally somewhere in the late nineteenth-century? One of the biggest problems with that idea, Mister Usher, is that I reckon that there are whole, affluent packs of doddering old biddies out there already who quite frankly can't get enough of Jan Fabre, Romeo Castellucci, Jerôme Bel, Forced Entertainment, The Sound Art Limo, or Sankai Juku..."

Thursday, November 29, 2007

Outta gas

Review: Not What I am: Othello Retold

For several years The Eleventh Hour has been one of the treasures of the Melbourne theatre scene. From their base in an enviably beautiful little theatre in Fitzroy, they’ve built an enthusiastic following.

And rightly so. Under directors William Henderson and Anne Thompson, this company – which exists entirely on private funding – has offered fresh interpretations of playwrights as various as Sarah Kane, Samuel Beckett, Oscar Wilde and Arthur Miller, with a particular emphasis on Shakespeare.

They create a fascinating form of stylised physical theatre, with inventive mise en scène and choreography. As far as I’m concerned, their robust approach to plays can sometimes be controversial – for example, an otherwise superb production of Beckett’s Endgame last year suffered from extra-textual interruptions.

But, agree with them or not, their productions are always intelligent, beautifully performed and superbly produced. Their radically reworked version of Othello, Shakespeare’s tragedy of the Moor of Venice, is no exception.

Not What I am – Othello Retold is a cut-and-paste of Othello which at times almost turns Shakespeare’s text into an oratorio.

Playing on the ambiguity of Moorishness, Othello (Rodney Afif) is Arabic rather than African. He and Desdemona (Shelly Lauman) form the central axis of the production. The rest of the cast – Iago (David Trendinnick), Emilia (Jane Nolan), Cassio (Stuart Orr) and Roderigo (Greg Ulfan) – doubles as a chorus, sinisterly cloaked in anonymous black.

The chorus represents Venice itself. They introduce themselves as the seven deadly sins, exemplified in Shakespeare’s play by Iago, one of his most charismatically evil characters. In this version, Iago’s wickedness is distributed through the populace of Venice, which collaborates to destroy Othello and Desdemona’s scandalously miscegenous marriage.

The lush design, a construction of Moorish walls and windows gorgeously lit in ochres and umbers, centres on Othello’s marriage bed. And from the beginning, the erotic marriage of sex and death is in the foreground: Othello’s final speech before he murders Desdemona is here performed as a seduction, exploiting the ancient pun that orgasm is a “little death”.

The other characters are as sexually charged as the central pair, drawing every erotic implication out of Shakespeare’s loaded language. As the tragedy nears its inevitable bloodbath, the production becomes almost hallucinatory, like a glimpse into Othello’s madness.

The excellent cast is equal to the extreme vocal and physical demands and is sometimes skin-pricklingly good.

As a colleague perceptively remarked afterwards, this is Othello as a revenge tragedy. Or, perhaps, as a spoken opera. Definitely one for the diary.

This review appeared in today's Australian.

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

McMullan for the arts?

Update: Nah, it's Garrett. Why, I ask (a genuine question), do I feel so unexcited? Well, let's see...

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

TN talks to Sheehy, the new face of MIAF

Usher has been a keen lobbyist against what he perceives as Edmunds' anti-mainstream programming. The most recent name he was gunning for was Brett Sheehy, whom Usher perceives as a director "more likely to return to a traditional programming mix". (Whatever that means.) He also suggested Lindy Hume earlier this year, prompting a sharp rebuke from MIAF general manager Vivia Hickman. And last night, festival president Carol Schwartz announced that Brett Sheehy is the successful candidate, and will helm the festival through 2009 and 2010.

Usher has been a keen lobbyist against what he perceives as Edmunds' anti-mainstream programming. The most recent name he was gunning for was Brett Sheehy, whom Usher perceives as a director "more likely to return to a traditional programming mix". (Whatever that means.) He also suggested Lindy Hume earlier this year, prompting a sharp rebuke from MIAF general manager Vivia Hickman. And last night, festival president Carol Schwartz announced that Brett Sheehy is the successful candidate, and will helm the festival through 2009 and 2010.So have the grinches won? Has the MIAF board blinked and gone for the commercial bling, despite the unqualified success of Kristy Edmunds' 2007 program? Or are they, perhaps, being very savvy? Your fearless reporter nailed the hapless Sheehy to the MIAF board table yesterday in order to investigate. And the result of my interrogation leads me to suspect that if Usher expects a sudden swerve to the "mainstream", he might very well be surprised.

I admit it, I was charmed. Although he had no doubt spent his morning being grilled by reporters, Sheehy showed no sign of weariness. His enthusiasm, which has almost a naive quality, is infectious. He says he is hugely excited and very nervous about his appointment. "I'm a huge fan of the Melbourne Festival, and I've attended every festival since 1992. Melbourne audiences are tremendously sophisticated and savvy, and it's a big challenge to present a festival here."

Sheehy has a long track record, and MIAF says he was the "stand out candidate" in their hunt for a new AD. Formerly literary manager at the STC, he's directed both the Sydney and Adelaide Festivals, winning various forms of kudos along the way. He's clearly good at attracting sponsorship - the 2008 Adelaide Bank Festival of the Arts, as it is now known, is the biggest arts sponsorship in South Australia's history.

But what are his plans for our favourite festival? "It would be insanely premature to say anything specific, especially given that Kristy has her own festival to run next year," he says. "But I am very conscious of the Melbourne Festival's Spoleto origins, and its international responsibilities. I am kind of... I am very ambitious and competitive for the organisations for which I work, I want them to strive for excellence in every possible way. And if I can do that, I know that Melbourne will be happy."

So far, so gold plated. But when asked what he thinks about Edmunds' programming, Sheehy is more than diplomatically polite. "Perhaps I'm a bit biased," he confesses. "I think Kristy Edmunds is a terrific artistic director, a terrific woman. But then, I've been programming people like Ariane Mnouchkine, Robert Wilson, Lucy Guerin, oh, for years.”

He is aware of the “vicious” commentary that Edmunds’s directorship has attracted – which he says that he doesn’t understand. “It’s not true, as some say, that she's changed her course,” says Sheehy, referring to the unanimous praise for this year's festival. “She's followed her vision from day one with a wonderful integrity and rigor." But he puts a positive spin on the debate. “On the other hand, it’s exciting that such robust and vigorous debates are happening,” he says. “And that there is this real sense of ownership of the festival in this city.”

Sheehy says he is keen to include organisations like the MTC – a notable festival absence – in his programming, while Usher notes approvingly that he’s all for symphony orchestras and operas. But I'm not panicking yet. It’s worth noting that this year’s Adelaide Festival includes Chunky Move and the Malthouse Theatre production of Marius von Mayenburg’s Moving Target. Mayenburg’s Eldorado, also directed by Benedict Andrews, was one of the works singled out by Peter Craven in a broadside against Edmunds last year, in which the “fringey” Malthouse was caught in the crossfire.

Sheehy, on the contrary, thinks the Malthouse is the most exciting theatre company in the country. To my surprise, he claims that the Malthouse has made waves across Australia, not just in Melbourne. “It’s a role model for all of us,” he says. “Recently I picked Michael Kantor as one of the top ten influential people in culture. It’s just astonishing what they’ve done here.”

Sheehy says a city festival is 50 per cent artistic vision and 50 per cent the milieu of the city itself. In Melbourne, as he says rightly, he can access an artistic community of richness and depth. There’s not much sign that he plans to change the festival's present direction in any significant way. He wants to plug into Melbourne’s visual arts scene and engender collaborations with other artforms, but that’s about as specific as he will get.

For now, he has to steer Adelaide 2008 first. He takes up his MIAF position on April 1 next year. In the meantime, he says that Edmunds’s 2008 program is “absolutely astonishing”. If it’s better than 2007, well, as incoming director, he’ll have to live up to that.

Sheehy will be seen as a “safe pair of hands” – the artistic equivalent of Kevin Rudd – but if he’s sincere about exploiting the vitality of Melbourne's artistic milieu he could be a very good strategic appointment, providing a period of consolidation. Perception is all, and a program strong on innovation under Sheehy – especially after the icebreaker years of Edmunds – might well defuse criticism before it occurs, and end up pleasing everybody. The proof is, as always, in the festival program he actually produces: but for the moment TN feels sanguine about MIAF. I think Sheehy's appointment is a smart move.

Oh dear...

Vague memories swim back - Wes Snelling singing 99 Balloons, Caroline Connors dressed up as a Christmas tree, my 12 year old son chatting up the evening's MC, Julia Zemiro, Rockwiz host but - of course - best known to TN readers as a rather superb Lady Macbeth. (He really did buttonhole her, astonishing the lot of us and eliciting much envy from his older brother. Ms Zemiro was charming. I think he's now officially in love). La Mama and its artistic director Liz Jones has a lot to celebrate: it's been a crisis year for this much-loved Melbourne institution, and they've not only come through, but come through stronger. I raise my glass - rather shakily - to Liz Jones and her loyal and hardworking team. As I remember through the spots, I raised it rather often last night. Glasses can't be raised often enough. La Mama is special, and we're lucky to have it.

It was, inevitably, also a de facto post-election party. Being packed with Brunswick arts extremists, it would have been hard to find a single person not delirious with relief at the defeat of the Howard Government. However, Ms TN had a couple of sober moments before she got to the Spiegeltent, and wrote a piece for the Guardian's theatre blog on government arts policies, up there today, in which she expresses her scepticism on Labor's approach to the arts. (I made the front page, just under George Monbiot! Oh gosh! The headline, I point out, is not mine own...)

PS: This scepticism reinforced rather than otherwise by the strange behaviour of Arts Queensland - a Labor State, remember -which supposedly is seeking to make "the arts sector more commercial and self-reliant" and has been causing huge problems for a number of its most notable organisations, including the acclaimed Elision Ensemble. H/t: Supernaut.

Review: Motortown

Motortown was written in four feverish days, at the time of the 2005 London bombings. British playwright Simon Stephens wanted to write, he says, a play “which inculpated more than it absolved. I wanted to write about my guilt in creating and perpetuating the culture that drove these wars…”

It’s the kind of impulse that can easily result in theatre that’s about as exciting as muesli. Thankfully, Motortown is too angry, too pitilessly honest and too sardonically funny to be earnest.

Motortown comes from a recognisable genre of plays that draw from George Büchner’s 18th century masterpiece Woyzeck, a play about an alienated returned soldier whose damaged psyche explodes in violence. As in David Mamet’s Edmond, the protagonist is in every scene, a kind of dystopic Everyman spiralling towards inevitable doom. He’s a symptom of a wider social sickness, a psychotic expression of a general moral vacuum that gnaws at the very heart of what it means to be human.

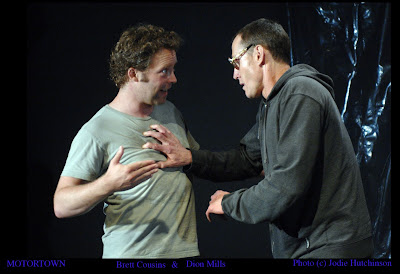

Danny (Brett Cousins) has bought himself out of the army after serving in Basra. Through his encounters with his ex-girlfriend, a petty arms dealer and some wealthy swingers, Stephens paints a scathing indictment of contemporary Britain. “The war was all right,” says Danny. “I miss it. It's just you come back to… this.”

These plays are also disturbing explorations of the crisis in masculinity that’s reflected, among other things, in a high suicide rate among men. Danny only admits how deeply scarred he is by his Basra experience in moments of crisis. This disconnection is linked to his compulsive lying; he seems incapable of telling the difference between fantasy and reality, and in part the play is driven by his different accounts of himself: a suggestion in one scene appears as a lie in the next.

In a particularly cruel scene, he is mocked by his ex-girlfriend Marley (Sarah Sutherland) for his impotence. His violence – like that of Woyzek or Edmond – is ultimately directed against women. But it's clear that Danny's problems predate his war experiences: the war only gives them horrifying expression.

As in Philip Ridley’s Mercury Fur, a recent hit in Sydney and Melbourne, the only real emotional connection occurs between brothers. Motortown begins and ends with Danny’s relationship with his disabled brother Lee (movingly protrayed by Dion Mills).

Laurence Strangio gives it a swift and powerful production, driven by a couple of excellent performances in the central roles of Danny and Lee. It’s not without flaws – some performances tend towards the mannered.

And Peter Mumford’s design – a floor painted in what I presume is crazy paving, with seatbelts suspended from the ceiling – is puzzling and distracting. But it’s a creditable production, and this spare, compelling play shines through with mordant clarity.

Picture: Brett Cousins (left) and Dion Mills in Motortown. Photo: Jodie Hutchinson

This review appeared in yesterday's Australian.

Saturday, November 24, 2007

Review: A Large Attendance in the Antechamber

Twist my arm even slightly, and I’ll break down and admit it: Ms TN is an unabashed fan of Mr Brian Lipson. His theatrical imagination has amused, intrigued and astonished me so much over the past three years that I’ve awarded him the Theatre Notes Seal of Approval (Class #1), a very pretty trinket that has myriad applications (eg, as a bath plug, a fishtank accessory or a very fetching hat). But up to now (I’ll whisper it), I haven’t seen his best known work.

A Large Attendance in the Antechamber premiered in 2000 and has had several seasons here, gathering enthusiastic praise along the way, as well as touring the festival circuit around the world. It even has its own Wikipedia page. Yet somehow, despite the glowing word of mouth, I missed it every time. This Malthouse season allows such delinquents as myself to catch up, and it seems I am not alone: the initial season booked out more than six months ago, and has been extended. Though it could be that it’s been booked out by those who want to see it again.

A Large Attendance in the Antechamber is a theatrical conceit concerning Sir Francis Galton, Victorian genius, founder of the controversial science of eugenics, discoverer of the anti-cyclone, inventor of the silent dogwhistle and cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton had the highest IQ ever recorded, though it seems that for all his brilliance, he lacked a little in what these days is called “emotional intelligence”. But this is as far from worthy biography as it is possible to get. Part scientific lecture, part séance, part slapstick and part theatrical essay, it’s riveting and intelligent theatre.

Lipson has made a kind of theatrical machine with which he investigates the workings of Galton’s mind. The title comes from a suggestive note of Galton’s, quoted in the program, in which he describes how he thinks. “There seems to be a presence-chamber in my mind where full consciousness holds court, and where two or three ideas are at the same time in audience,” he says. “And an antechamber full of more or less allied ideas, which is situated just beyond the full ken of consciousness…. The successful progression of thought appears to depend, first, on a large attendance in the antechamber.”

It’s a striking description that suggests the possible anarchy of the subconscious (those attendees in the antechamber are often a ragged and disreputable lot). The connection to Berggasse 19, Lipson’s wonderful conceit about Freud's psychoanalysis, is immediately obvious. Both works have a fascination with the ellipses and eruptions of the subconscious, and both are intricately designed shows with an obsession with objects. The set for Antechamber seems to be have been made out of a packing case, the interior of which is a simulacrum of Galton’s study, complete with oil lamps, ceiling rose, hat stand, pictures and strange instruments that are produced, like rabbits out of a hat, out of the crammed interior.

Galton – complete with sideburns, Victorian dress and high forehead – is waiting for us as we arrive, seated in his absurd box. When he begins to speak, it is to apologise for what he considers an unsatisfactory presentation – he is being impersonated by an actor. And so begins the long series of conflicts between Sir Francis Galton – the speaker – and his rebellious subconscious, the actor Mr Lipson, who clearly is outraged by some of Galton's ideas.

It’s a conflict that escalates throughout the show with increasing absurdity: since it is Galton who, as it were, holds court, Lipson’s presence is reduced to subversive gestures – notes pinned to Galton’s back perhaps, or suspended from a helium balloon. At one point, he invents a ridiculous mechanism by which to introduce the actor without actually breaking the conceit by speaking his name; at another, he arrests himself; at another we are presented what is surely the most devastating parody of blackface I have seen, fatally undermining Galton's account of his adventures with the Hottentots in Africa.

The ostensible subject matter – a kind of whistle-stop tour of Galton’s achievements – is fascinating in its own right. Galton lectures on the necessity for selective breeding to achieve the potential of the human race, on ideal female beauty and on how to make a perfect cup of tea. He gives a slideshow in which he demonstrates the creation of a virtual woman – a woman created with the new photographic technology out of the features of different sisters. Using the same technique, he creates a generic image of the "Jewish type". And later, underlining the instablility of performance, he melds Lipson’s face and his own photographic image to create a third creature, the fiction being created before our eyes in the theatre.

It was, of course, Galton's idea of eugenics, or selective breeding, which was picked up and obscenely taken to its logical conclusion by the Nazis. In this show, it's clear how the idea stems out of the British class system (a certain class has always insisted that its sons and daughters, like its horses, exhibit "good breeding"). Our - and Lipson's - awareness of this darker subtext gives a sharp and discomforting edge to Galton's eccentricities. Galton was of his time: racist, sexist, a firm believer in the Victorian virtues of categorisation, the imperial virtues of discovery and the superior qualities of the British male.

For all its slapstick subversion, Lipson's show evades mere caricature. Its playfulness, a series of mirrors within mirrors within mirrors, is deeply serious: it asks us to be conscious of the artifice of theatre, and becomes ultimately a metaphor for the performances and masks of the self. Beneath Lipson's portrayal is a constant and uneasy subtext of madness, an unexpressed pain that occasionally breaks the surface in some throwaway image of Galton's (his description of sanity, for instance, as a tabletop surface with no safety rails).

In its final few moments the entire theatrical conceit is dismantled before our eyes, and leaves us unsure whether we are looking at Sir Francis Galton or Mr Brian Lipson. Or perhaps we are given a glimpse of someone else, a man denuded of all titles and labels and masks, a strangely anonymous human being who is simply exhausted at the end of a demanding performance and, trapped in the gaze of his audience, is unsure how to finish it.

It's one of those moments when the artifice of theatre becomes a means of revelation; although a very different kind of theatrical epiphany, it's not so far from Lear's vision in the midst of storm, in which man, stripped of his hubristic self-importance as the centre of the universe, is revealed to be only "a poor, bare, fork'd animal". It's the kind of risk that can only be ventured by an actor as accomplished as Mr Lipson. It might require all his skills to get there, but this kind of exposure is not about the art or the craft of acting, but about the sort of courage that is prepared to destroy both.

Picture: Brian Lipson in A Large Attendance in the Antechamber. Photo: Lisa Tomasetti

Election jitters

Little Miss Alison has had a difficult week. My synapses have been dangling forlornly in empty space like shorting cables, and the crease in my forehead has been more suggestive of terminal stupidity than of signs of intelligent life. I think I caught the virus that I so successfully avoided during the Melbourne Festival. Anyway, I've been feeling miserable. It's very badly timed: I have a big black novelish deadline coming up at the end of the month, and a few thousand coherent words to smith before then (but a review of Mr Brian Lipson's and Sir Francis Galton's extraordinary A Large Attendance in the Antechamber coming up soon, I swear).

But I think I've also got the jitters. I'm not sure I've ever felt so anxious about an election. The thought of the Coalition continuing in office seems unbearable, and I almost daren't believe they will lose. I've even become an obsessive psephologist. Goddamit, Australia: surely it's time to kick these sneeringly complacent moral bankrupts out of office?

Thursday, November 22, 2007

Hard lines

Meyrick is leaving the company at the end of this year to assume a post-doctoral research fellowship at La Trobe University. As yet there's no word on who will be replacing him. (Or, indeed, if he will be replaced: the MTC website says that "currently there are no positions available at Melbourne Theatre Company". Although we also note that the information on Hard Lines dates from last year...)

This year, writers supported by Hard Lines won major awards - the Patrick White (Patricia Cornelius), Wal Cherry (Ross Mueller) and Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards (Jane Bodie) - which shows that Meyrick has an eye for talent. He'll be speaking about his experiences with new Australian drama and the aims of the MTC's development program after Wednesday night's reading.

$5 entry, students free, at the Grant Street Theatre, Victorian College of the Arts, at 6.30pm on November 27 and 28.

Monday, November 19, 2007

Review: Letters from Animals

Kit Lazaroo, who’s been quietly gathering plaudits and prizes since 2003, has been sitting in my mental filing cabinet with the stamp “must investigate” for some time now. Big red stars in texta were drawn on the file after the sell-out season of her play Asylum at La Mama last year, of which much praise trickled Williamstown-wards. Well, I might be slow, but I get there in the end.

It’s hard to know where to begin with Letters from Animals, now on at the Store Room in a simple but beautifully realised production. It’s much more difficult to write about than it is to see; it's a delicate, complex work that can seem merely whimsical, when in fact a bleak and uncompromising intelligence runs through it like a steel rod. Perhaps it’s an indication of its richness that this play prompts comparisons in so many directions.

Lazaroo is one of a number of noteworthy new playwrights presently enlivening Melbourne’s stages (others include Lally Katz and Ross Mueller), although her imaginative diction also reminds me of Sam Sejavka, who has been writing since the 1980s. And these writers have something in common with others further afield, people like Britain’s Philip Ridley or Germany’s Marius von Mayenburg.

For all their variousness, these playwrights reflect a sensibility that seems to me quite particular and of our time, but I’m sniffing: I’m not quite sure how. I suspect it's partly to do with a certain formal playfulness, a post-television consciousness that returns to the basics and throws them up in the air for questioning; but they also have an underlying darkness, an uneasiness that reflects contemporary anxieties and uncertainties. All of them approach the world elliptically, avoiding the easy statement, the play-as-message; but that can be said of every serious artist. And certainly, all of them are writers who understand the inherent poetic of the theatre.

Letters from Animals is several things. It’s a sorrowful and absurdly comic fable on memory and forgetting; a bleak warning about stupidity, greed and treachery; a satire on bureacractic oppression; and a lament of considerable lyric power. One of the admirable things about it is how it keeps so many things in play at once, so nothing ever quite comes to rest on a conclusion.

It's set in an imagined future, in a world in which animals no longer exist. This is a world destroyed by pollution and global warming, flooded with poisonous water and “sludge”. The only living things on earth are human beings. Or, more precisely, women: there seem to be no men at all. No doubt they have mutated out of existence thanks to the oestregen in the water and perhaps the women all reproduce by parthonogenesis: the playwright doesn’t say. Every other living thing has been eradicated, as harbingers of disease and uncleanliness from the "Days of Filth".

Queenie (Glynis Angell) is a former scientist living on the margins of society, who is attempting to restore the animal world from the few fragments – biological and semantic – that are left. This is subversive work in a world run by the sinister and faceless Developer; here people are controlled by regular inoculations which wipe their minds clean of memories and dreams and guard them against the possibility of remorse. Queenie is being investigated by the bureaucrat Shelley (Georgina Capper), who sends the young and ambitious Gretel (HaiHa Le) to spy on her activities.

In the meantime, the animals themselves – in the form of a Rat, a Vulture and a Cockroach – are demanding their return, perhaps even planning a revolution. It is never clear whether the animals exist independently or as alter-egos of the three characters; in the oneiric logic of this play, they are both. And, being peculiarly literary animals, they are sending letters to the women, asking to be remembered, to be restored, to be mourned.

Most of all, this is a play about language: the extinction of our fellow creatures is reflected by a linguistic and, crucially, an emotional impoverishment. As we lose their names, their descriptions, so we lose the ability to understand ourselves. Animals are everything that escape human order and human law; but they are also in us, in our animal selves, and with us. In the terrible future imagined here, they need us. Or is it simply our need speaking through the memory numbed by their absence? As the animals say in one of the letters that mysteriously haunt the bureaucrat Shelley:

Unaccustomed as I am to putting pen to paper. I find myself in need of your assistance. I trust you haven’t forgotten me. I cut your foot once when you went swimming. You looked through the boards of the jetty and watched me push against the current. I was in a cage at the zoo. I lived under the roof of your house. I ate food from your bin. You saw me resting in the mud. You caught me in a glass jar and put me on a windowsill. I fell out of a tree when the sun was hot and spat at your feet. You kept me in a shoebox under your bed and fed me the wrong leaves until I died. Don’t forget me. Bring me back. Speak my name.

Balancing the comedy, pathos and mystery of a play like this is not an easy ask, even in the best of circumstances, let alone in the confines of the Store Room. Here Theatre pulls it off admirably. After the theatrical excesses of The Madwoman of Chaillot two nights before, it was an inexpressible relief to be reminded that it really is true about two planks and a passion.

What counts most in making this imaginative world are the performances, and all three actors are equal to the task. Georgina Capper in particular, in the double role of the disintegrating bureaucrat Shelley and the French Vulture, is an actor I want to see more of. Director Jane Woollard deftly evokes Lazaroo's elliptical realities with the help of a lot of smoke, Bronwyn Pringle’s ingenious lighting, several buckets and an evocative sound design.

It’s an exemplary demonstration of how theatre can be political and contemporary without being didactic or simplistic. In short, it rocks.

Picture: Glynis Angell and HaiHa Le in Letters from Animals.

Elsewhere in Melbourne

Sunday, November 18, 2007

More politics

I had my own meditations yesterday, responding to Hilary Glow's new book on theatre and politics, but mainly the blogosphere is awash with responses to Jay Rayner's piece on the pressing need for right wing theatre "to take on the establishment". I'm kind of with George Hunka here: as he comments dryly, "if you want to fuss, fuss". George picks up on David Hare's bizarre comment about Samuel Beckett's "prettified acceptance" of suffering - an offensively mistaken view of Beckett, in my view, and amply countered by Trevor Griffiths' suggestion that Beckett was the most political playwright of his era (this via Abe Pogos). This kind of discussion sends me into catatonia, I'm afraid. It seems to comprehensively miss the point about theatre and politics, and I start wanting to instruct everybody to go back and read Susan Sontag again. But maybe missing the point is the point. I'm not sure.

Not that I'm against the intersection of theatre and politics; I just wish the terms were more interesting. So I'm glad to see that Lyn Gardner from the Guardian got along to Honour Bound in London and gave it a four-star rave, despite my esteemed colleague Mr Boyd predicting that it would be greeted with "contempt". (What was that conversation, Chris?)

I guess you're all sick of politics by now. Good. Let me point you then to a must-read - George Hunka again, this time on the blog at Ontological-Hysteric Theatre observing Richard Foreman in rehearsal. That'll scramble your binaries for you.

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Playwright as social symptom

What's shifted is the idea that theatre is primarily a socio-political document, and primarily the home of naturalism. The focus has moved from issue-based plays to a more multivalent awareness that representation itself, in this media-saturated world, is a deeply political issue, and that it is not nearly enough merely to state the issues. ...Puzzling over the claim that theatre is less political, when it is so manifestly not the case, I suspect that this shift away from naturalistic issue-based plays is the change that Glow notes, and mistakes for a lack of political engagement.

In the ensuing discussion, Ben Ellis, one of the playwrights interviewed for the Power Plays, pointed out, very reasonably, that Glow has every right to set her terms of discussion. "I think," he said, "that Hilary's choices allow her arguments about politics and theatre to be focused." And of course, it was unfair to speculate without having read the book. Surely the book is making a self-fulfilling argument in accepting those assumed limitations? The STC has been hosting things like Howard Barker's Victory, or Kosky's The Lost Echo. Benedict Andrews's production of The Season at Sarsaparilla critiqued modes of perception in its design and direction. And the politics in next year's STC program is quite difficult to escape, although at least a third of it eschews the naturalistic model of "unified narrative, psychologically plausible characters and emotional engagement" (although I always hope for emotional engagement). Which at the least brings into question the idea that the formal choice of naturalism has to be observed in order to be programmed. The mix gets more complex when you look at all the theatre companies supported by the Major Performing Arts Board, which include the Malthouse and Company B, as well as Bell Shakespeare and all the State companies, and if you include the Melbourne Festival. This insistence on a very limited view of "mainstream" theatre - and the associated claims for its political significance, which underlie this book's argument - is a critical weakness. Even on her own terms, Glow uses "mainstream" very loosely: sometimes, as in the introduction, "mainstream" becomes a synonym for "play". It's muddied further by Glow's many discussions of independent theatre or independently produced plays, such as Ilbijerri Theatre, The Keene/Taylor Theatre Project or Melbourne Workers Theatre. Why insist so strongly on the definition of "mainstream" in the first place if, in the body of the book, it means so little? It is hard to see it as anything more than a rhetorical claim. There are other strange acrobatics. Glow has already claimed that theatre's highest good is as a public forum for informed political discussion. She has a fair bit of trouble squaring this instrumental view of art with her own objections to the equally instrumentalist economic rationalist model that she objects to from the Howard Government, but solves the contradiction by ignoring it. Instrumentalism is, it seems, ok if in the service of one kind of politics, but not in another. Likewise, Glow quotes Terry Eagleton on ideology, which he says constructs a "reassuringly pliable" view of the world, and then speaks of theatre's capacity to unsettle ideological frameworks; but she nowhere questions the ideology adumbrated in the book. And this is an avowedly ideological argument, as expressive of a heterodoxy as anything it argues against. I finished Power Plays with the gloomy thought that this book reduces theatre and art as effectively as any argument by Andrew Bolt: it employs the same parameters of discussion, and merely mirrors the effect - left wing, instead of right. Passion, intellectual play, love, formal curiosity, actual social engagement, the very experience of theatre itself, seem very far away. No wonder "we no longer feel", as Glow says, "that theatre is as important as life itself". I hope some of you took advantage of Currency's generous offer last month, and bought and read the book. Now I've had my say, I'm fascinated to hear yours.

Well, now I have read the book: and then I re-read my earlier post and thought, damn right. But I have promised to discuss Power Plays, so I will, though I confess to some reluctance. I should point out at the outset that my response is no reflection on any of the playwrights mentioned in this book; that would be another post.

I tried, Ben, I really tried. It is only fair to read any book on its own terms, and I did make a brave effort. My problems begin with Glow's defining of her choices and her definitions of important terms. Her argument is so muddy, so riven with self-contradiction or received assumption, that it almost makes no sense at all. If you are to argue with something, you need an argument to argue with. I disagree, for example, with Michael Billington on many salient points, but Billington always creates an intellectual structure with which it's possible to disagree. And besides, he's a pleasure to read. I don't feel any such clarity about Glow's book.

My problems with Power Plays are on two levels. On one, I disagree with almost every critical assumption about writing and politics and theatre that Glow makes in this book. On the other, quite aside from my own take on these things, the book makes an argument that is often incoherent, and reaches conclusions that are often, on inspection, disappointingly banal.

It's the kind of critical writing about theatre that makes me deeply depressed. It demonstrates the pedestrian ideological mindset and intellectual shallowness that strangled Australian theatre through the 80s and 90s. It is hard to know how to begin to talk about it, partly because its argument is so unclear; so I thought I'd just briefly pull out some individual points.

Power Plays discusses primarily the work of eight playwrights - Stephen Sewell, Hannie Rayson, Katherine Thompson, Andrew Bovell, Ben Ellis, Reg Cribb, Wesley Enoch and Patricia Cornelius - whom Glow interviewed for the book. But she by no means confines her discussion of political theatre to these playwrights: in fact, there is a dizzying sampling of Australian plays and playwrights discussed in this book, from Richard Frankland to Michael Gurr, from Oriel Grey to Jack Hibberd.

Taking a leaf out of Leonard Radic's Contemporary Australian Drama, Glow approaches theatre primarily as a means of tracking social history: "This book contends," she says, "that the Australian theatre of the last decade has been a good place to find out 'what is really happening'." And she is concerned with plays that, as she puts it, reflect a "critical nationalism", which works "against the grain" of John Howard's vision of "One Australia". The writers of these plays "insist", she says, "that their highest motivation is to provide politically informed debate on key issues in the public domain". She is not writing a history of all political theatre, and she is not writing a history of performance.

The problems begin when she starts to adumbrate her definition of "mainstream". She is concerned with "mainstream" playwrights "whose work is performed in and by the leading state-subsidised theatres in Australia" to "middle-class, aging" audiences. "Mainstream" plays are further defined as naturalistic, character-based dramas: they alone "engage with forums of power" and reach a national audience.

Nothing in the book answers my earlier questions about this definition of "mainstream", which I might as well repeat.

The examples I've noted seem to me to be quite noticeable eruptions of political critique in mainstream venues that, yes, absolutely have to get those bums on seats, but are still exploring work that reaches beyond the model of dramatic naturalism. Isn't an important part of this discussion that the parameters of the "mainstream" have noticeably been changing over the past few years?

The definition of "political" is similarly problematic. After some discussion of the difficulty of defining political theatre, Glow accepts that political in this context means "the interrogation of systems of power". This might work if the book were more aware of, and interrogated, the systems of power at work in Australian theatre, but these remain largely unaddressed.

Glow has, for example, some strange ideas about agency: she says several times that writers "choose" to be mainstream playwrights. Hannie Rayson, it seems, "chooses" to have her plays performed at the MTC, rather than, say, at La Mama (oddly, given its noble history of political theatre, not mentioned in this book). Even the briefest consideration suggests that it is the MTC that chooses, otherwise we'd have mainstream playwrights coming out of our ears. No doubt this confusion stems from Glow's conflation of a formal style - naturalistic plays - with her definition of a category of theatre - theatre made in special buildings for middle-class audiences. But it is indicative of a general fuzziness.

Worse, this definition of the political as interrogating systems of power could be applied to almost every play ever written. Glow localises it by bringing in the notion of "critical nationalism": she is concerned with plays that argue against the prevailing nationalism promoted by the Howard Government. The danger of Glow's argument becoming purely reactionary ought to be obvious; especially if, as is widely expected, Howard gets voted out in a couple of weeks.

It is also very parochial: our theatre only counts as political in this purview if it explicitly addresses our "Australianness". There is no discussion of political theatre writing here in any wider context: you will look in vain for any references to Edward Bond, or Howard Brenton, or Augusto Boal, or even Bertolt Brecht. (David Hare gets a couple of mentions, but only because he visited Australia, and Samuel Beckett gets a very small guernsey in a discussion on Ben Ellis). One very serious problem with this book is that, while it might have a lot of breadth in the range of Australian theatre it discusses, it has hardly any depth at all.

Friday, November 16, 2007

Now for the numbers...

This year MIAF's total ticket sales were 76,897 - up around 16,000 from last year, and in the Leo Schofield ballpark of between 60,000 and 80,000 deemed desirable by chief festival Grinch Robin Usher. The average ticket price is an astoundingly low $29. And MIAF lists a long drumroll of shows that were sold out or at near capacity. The estimate for total attendance to all free and ticketed events, which the festival says is incomplete as figures are still coming in, is 475,000. Not bad for an event in a city of 3 million people that was said to interest nobody at all.

Total box-office return was $1,967,960. This will be the only figure some critics will look at, comparing it unfavourably with the Sydney Festival's $4 million, as if the success of an arts festival is only measured by economic profit. I guess it depends what you think an arts festival is for: after all, Sydney's program is avowedly more populist.

I don't want to miff my Sydney friends, but I can't say that the 2008 dance and theatre program has made me rush out to book my plane tickets up north. For one thing, we've seen quite a few of the Australian productions here already - five, by my count - a couple as MIAF premieres. And the program shows that if you want a $4million return, you don't headline Merce Cunningham or Peter Brook or Robert Wilson; you bring in Bjork and that other Wilson from the Beach Boys. Nothing against Bjork, we love her here, but the music program looks like the Big Day Out.

Review: The Madwoman of Chaillot

We all have them. Those mornings when you wake and recall the events of the previous evening with the desperate hope that it was all a dream. You call your friends to check the facts: was it really that bad? And, very gently, they tell you that, yes, it was.

I had one of those mornings yesterday. On Wednesday night I went to see The Madwoman of Chaillot at the MTC. I entered the theatre with sprightly step, my eyes shining with hope; and three hours later I emerged a broken woman, with the kind of headache that follows a night of concentrated debauchery. My objection to this is that I suffered all the punishment with none of the fun.

It could have been a charming nonsense. The play concerns a cast of colourful Parisians – street singers, jugglers, friendly gendarmes, and so on – led by the madwoman of the title, Countess Aurelia (Magda Szubanski). They lounge picturesquely around their favourite café while a wicked Texan prospector (played by Julie Forsyth in a large black moustache and ten-gallon hat) announces that he has sniffed oil under them thar Parisian hills and, backed by the evil machinery of capitalism, is planning to turn the City of Light into an oilfield.

With the help of a great deal of absurdity, the plot is worsted, greed and corruption are banished from the world and good triumphs. The play is a defiant bauble thrown into the face of bleak reality – Jean Giraudoux wrote it in 1942, in the depths of the Nazi occupation of France. And director Simon Phillips has assembled a cast that includes some of the best comic actors in the country. So what went wrong?

The details swim back to haunt me. Stephen Curtis’s set was like a Yoplait commercial: no cliché was left unturned. Was Paris ever so embarrassingly portrayed, outside a souvenir shop? I am sure I dreamed of the Eiffel Tower: there are a lot of Eiffel Towers in the set, painted on screens and curtains, just in case we miss the fact that this play is set in Paris.

To make absolutely certain we aren’t lost, most of the cast affects a motley assortment of French accents and quaint Gallic gestures. Szubanski is mercifully accent-free but, unlike the others, wears a radio mic. (This complements the tish-boom sound design nicely). There are moments when the actors manage to transcend this overdressed, heavy-handed production, but they’re pushing against the tide.

A scene between Szubanski, Sue Ingleton and Julie Forsyth, in which they play three mad old women with an imaginary dog, suggests what might have been possible; some real comedy began to emerge from the mannerisms. Sewn into the dialogue is a witty meta-theatrical commentary on its own fiction, of which absolutely nothing is made in the production. Among other brighter moments, Alex Menglet has a turn as a sewerman, and Michael Butel as the Ragpicker delivers a frenetic speech in defence of capitalist nastiness. But any signs of life are swiftly muffled by a suffocating froth of fuss and frills.

Phillips fills the stage with colour and movement, but with little else. In fact, there is so much colour and movement it is sometimes hard to follow the play. The text itself is a US adaptation, with Wall Street capitalists replacing the original Nazi bad guys, and so is punctuated with rather puzzling American references and what are – I think – moments of purely New York humour. I guess it’s 1940s New York humour: Maurice Valency’s adaptation, which was later made into a 1969 film starring Katharine Hepburn, dates from then. The jokes don’t translate to 2007 Melbourne, and contribute to the general feeling of heaviness: but I still don’t think the play needed to feel quite as long as it did.

There are touches that recall the lightness with which Phillips can direct: at the opening of each act, for example, the characters in a scene are backlit behind the curtain, briefly seeming like a group of daguerreotypes. But the feeling and flair that characterised his marvellous 2005 production of Cyrano de Bergerac is little in evidence. I’m not sure that I’ve ever spent such an empty a night in the theatre.

A shorter version of this review is published in today's Australian.

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Chat amongst yourselves...

Fortunately, my fellow bloggers are filling in any airtime I leave free with some fascinating discussions. The Guardian theatre blog page is becoming a must read: it is being colonised by some of my favourite bloggers. George Hunka makes his debut today with a piece on playwrights whose work is more often performed outside their home country, including our own Daniel Keene; and Andrew Haydon continues a series of debates on the relationship between theatre and politics with a post on "a state of near civil war" he perceives in British theatre at present between "proper theatre" and what is, I suppose, improper theatre.

I can't resist adding here that in Europe, Australia has always been linked with impropriety: as the critic Louis Armand says, "Australia, it should be remembered, was first and foremost the destination of those who were considered to have insulted the law of property, it was dispossessed of those who failed to recognise the law of property, while [the environment] itself was consistently hostile to the idea of property - just as it has always been hostile to an aesthetics of the 'proper'." Of course, this is only partly true: colonial anxiety has also made some aspects of Australia proper to the point of vulgarity. But the strangely fraught question of what is "proper theatre" strikes me as being as of much interest in these here parts as it is in the northern hemisphere.

Monday, November 12, 2007

Australians in London

Update: more reports from the Old Country: confederate rebel Andy Field takes off his bandana for a moment to see Small Metal Objects.

The Malthouse goes green

But as for the season - my picks are Tartuffe (what is it with Tartuffe this year?) directed by Michael Kantor and Moving Target, a new play from Marius von Mayenburg commissioned by the Malthouse and the Sydney Opera House and directed by Benedict Andrews, the same team who brought us the brilliant Eldorado. Though Through the Looking Glass, with a libretto by the ubiquitous Andrew Upton and score by Alan Johns, and Venus and Adonis directed by Marion Potts, attract my eye as well. (Lots of co-productions here). As their offering to the Comedy Festival, they've picked up another Anne Browning/Peter Houghton collaboration - the same team who brought you The Pitch - from La Mama, with The China Syndrome. Oh, and don't miss Oscar Redding's miraculous film of Hamlet. I think that's the whole program.

More importantly - you know how narcissistic us bloggers are - the program prints a long list of bloggers under the heading "More Engagement". "Recently, we debated the virtues of a more chat-based space for our audiences," says the Malthouse. "In reality, there are already a host of independent blogs bursting with opinion and rattling the cages of certified criticism, and on which you can post your comments... Rather than compete, we thought we'd list some of the blogs we regularly visit." And so they have, in democratic alphabetic order. My god, a theatre more interested in discussion than in praise. Brilliaaant!

And as an addendum, TN notes that her campaign to reunite poetry and theatre is bearing instant fruit. This Wednesday, two shows open that feature two of her favourite poets, Sappho and Emily Dickinson. (This isn't quite what I meant by poetry in the theatre, but it's a good start). The irony is, of course, that given a rather intimidating deadline on a big project that has nothing to do with theatre, I might not be able to make either of them.

Thursday, November 08, 2007

Coupla things

Details: $5 at the door, 4.15pm – 5.30pm on Sunday November 11, Fortyfivedownstairs, Flinders St, City. RSVPs requested on 9662 9966.

Second, last night the Malthouse launched what promises to be a most fab season 1 for 2008. Richard Watts mysteriously says it's embargoed - nobody told me, and it all looked very public, but you know me and embargoes. UPDATE: yup, it really was embargoed, so Ms TN has politely removed those (minimal) spoilers until Monday. Embargoes have to be shoved under my nose in nice big texta, I suspect.

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

Poetry and theatre

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

Knuckling down

And while you're at it, check out Carl Nilsson-Polias's blog, which I'm ashamed to say has not swum my way before, since he's been writing it since 2001. It's chockful of reviews, fascinating meditations and even interviews - for you many fans, the interview with MIAF favourite Jérôme Bel is a must-read.

Meanwhile, over at The Arcades Project and on the Guardian blogsite, Andy Fields teases out more on the politics of theatre (on which there is a most interesting convo below, with I hope more to come) and Mr Superfluities George Hunka buys into the form/politics question with some thoughts of his own about tragedy - "in exploration itself is political meaning". And while the conversation is boiling, Postcards from the Gods bod Andrew Haydon has another Guardian post asking stern questions about private sponsorhip. That should keep you all out of trouble. Or get you into it. Depending.

Ursula Le Guin

Language has always been central to the serious magic of Le Guin's work. In a short passage called 'A Few Words to a Young Writer', she says:

Socrates said, 'The misuse of language induces evil in the soul.' He wasn't talking about grammar. To misuse language is to use it the way politicians and advertisers do, for profit, without taking responsibility for what the words mean. Language used as a means to get power or make money goes wrong: it lies. Language used as an end in itself, to sing a poem or tell a story, goes right, goes towards the truth.

A writer is a person who cares what words mean, what they say, how they say it. Writers know words are their way towards truth and freedom, and so they use them with care, with thought, with fear, with delight. By using words well they strengthen their souls. Story-tellers and poets spend their lives learning that skill and art of using words well. And their words make the souls of their readers stronger, brighter, deeper.

As a writer and reader, I find this statement inexpressibly moving in its directness and wise courage. And it also points to the deeply radical impulse that lies behind Le Guin's work.

Full transcript and audio here.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Review: A Dollhouse

When you read novels and plays from the late 19th century, it is sometimes a little depressing to discover how much intellectual discussion then has in common with what we argue about now. Women still complain about being infantilised or of being valued only for their appearance. Probity is still only a problem for a businessman if he’s caught in wrong-doing and publicly exposed. We still worry about materialistic values and imperalistic injustice and even whether God created the world. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

Henrik Ibsen is a case in point. When he was writing A Dollhouse, he told his friend Hegel that it was “a play of modern life”. And its modernity is still striking: there may be the odd porter and housemaid, but the action begins with no preambles and runs cleanly to the end, and there are surprisingly few opinions expressed by the characters that would sound amiss to a contemporary ear.

In this VCA production, director Daniel Schlusser has taken Ibsen at his word, and delivered a modern play. A Dollhouse is set in contemporary Melbourne, in a converted warehouse apartment, and Torvald (Nick Jamieson) has just landed a top job at the Macquarie Bank. In his spare time, he enjoys yoga and Playstation. Nora (Katherine Harris) is a funky yummy mummy who likes a bit of shopping therapy. Some of their dialogue, peppered with the standard casual obscenities, would have given 19th century theatre critics – who were shocked enough by the idea that a woman might not submit to her husband – severe conniptions.

But I was surprised, reading the play again afterwards, how little of the text was changed. This production’s disrespect is wholly in the service of the play. As he says in the program, Schlusser’s intention is to recapture Ibsen's original radicalism. It’s impossible to wholly regain that moment when the slam of the door as Nora left her loveless marriage was said to echo through all Europe: but this is an intelligent look at a classic play that scours off the cultural verdigris and shows it to be as sharp as ever in cutting through the superficialities and deceits of contemporary mores.

Instead of observing its naturalism– in Ibsen’s time the radical edge of modern playwriting, but now so worn a convention we barely see it – Schlusser opts for an aggressive theatricality that exposes the mechanics of both the play and its staging. When the play opens, all five actors are on the narrow metallic set, which runs the width of the theatre. The sound deck is to the right of the audience, playing loud pop music. The wall at the back of Jemimah Reidy’s set is punctuated with a series of hatches, the wall-louvre of a gas heater, a door made of zipped fabric and a television screen set into the wall. As the play proceeds, the set gets more and more littered with the throw-way kitsch of consumer culture, and, of course, with toys (quite a lot of Lego, which is, after all, impeccably Scandinavian).

A voiceover recites Ibsen’s stage directions, and the actors launch into a brief comic aside that contextualises when A Dollhouse was written (and even perform a little of it for us in the original Norwegian). The actors begin to argue, and as their voices rise, so does the music, until Torvald screams at the sound technician to turn it down. Once the artifice of what we are watching is established, the play can properly begin: but now we’re consciously watching it at several levels. Nora’s performance as Torvald’s little lark is also, for example, a 21st century performance of attitudes that are conditioned by 19th century mores.

It’s classic alienation effect which, crucially, intensifies rather than removes the feeling of the play. When Brecht coined “Verfremdungseffekt” to describe his epic theatre, the idea was to heighten an audience’s critical consciousness of what it was watching; but it is a mistake to deduce from this that critical awareness is the same as refusing feeling. Rather, Brecht wanted the reverse: as he says elsewhere, “grab them by the balls, and their hearts will follow”. And this is in fact a deeply moving rendition of A Dollhouse.

Neither Schlusser nor his fine cast step back from the play’s complex passions, and the crucial dialogues are played straight. This production is notable for excellent performances from each of its five actors, beginning with performances of detail and depth from Harris and Jamieson as Nora and Torvald. When Dr Rank (Ben Pfeiffer) confesses his love for Nora, or informs her of his impending death, the scenes are pregnant with what is not said, and what must not be said. The love scene between Nils Krogstadt (Michael Wahr) and Kristine Linde (Edwina Wren) has the complex sadness of experience and failure. The final quarrel between Nora and Torvald – a sharp portrayal of self-blindness from Jamieson – is searingly painful.

Perhaps the most interesting decision is to adopt Ibsen’s rewriting of the end of the play. It’s had me thinking for days. When the play was first written, Ibsen was told in no uncertain terms that it was impossible to present the play with an unhappy ending. Rather than have his play butchered by other hands, Ibsen opted to perform “this barbaric deed of violence” himself. In this version, Nora is forced to look at her children, and finally cannot bear to leave them and, as translator Peter Watts says, "sinks to the ground as the curtain falls with masculine supremacy restored and Woman relegated to her proper sphere of 'Kirche, Küche and Kinder'."

The effect in this production is entirely different. As Nora storms out, there is a pause, and Torvald calls her name. He is holding in his arms a little girl, their daughter, and slowly Nora turns and comes back; and the play ends with all three embracing. It’s an ambiguous and complex moment, and the effect after the awful scene beforehand is the reverse of sentimental. In a time when it would be standard practice for the wife to leave, Nora’s recognition of the experience and embodied love she shares with Torvald has more power to surprise than the original ending. It is the moral alternative to the empty materialism that has characterised their relationship. And far from being defeat, Nora's return is an act of hope.

Picture: Katherine Harris and Nick Jamieson in A Dollhouse. Photo: Ponch Hawkes

What is it about writers?

So I see with a mixture of puzzlement and alarm that Michael Gow has written a play about writers block. Toy Symphony - which "attempts to capture that terrible thing that stops the act of writing" - follows his 1991 play Furious. Furious was about the same playwright (Roland, presumably Gow's alter ego), this time in the throes of inspiration. I don't know about you, but when I saw Furious it confirmed my growing suspicion that plays about writers ought to be banned. Writers are not good dramatic material. Let's face it, all that fussing about with paper and keyboards isn't exactly exciting. A play about a writer not writing might be even worse than one about a writer writing. I don't know. (One shouldn't, of course, prejudge, but I'd be trotting along to Belvoir St with some trepidation). I'm more interested that Gow is directing Heiner Muller's adaptation of Titus Andronicus for Bell Shakespeare later this year. Heiner Muller. Now, there's a writer.

Saturday, November 03, 2007

Amo, amas, amateur

No, we can't... The article is mainly a clear-eyed but fond tribute to Neville Cardus, the now forgotten music critic (and sports writer) for the Guardian through a large part of the 20th century. He was, according to Teachout, a half-century too late: the perfect critic for Romanticism, the 20th century revolution in music left him cold, and finally left him out. But Teachout persuasively argues Cardus's responsiveness to and love of the art, and comments: "something vital disappears from criticism when its practitioners are unwilling to approach music in this way".

H/t: Playgoer.

Friday, November 02, 2007

Review: The Chosen Vessel

In the Dictionary of Australian Biography (1946 edition), Barbara Baynton gets fairly short shrift. After noting her three marriages, Percival Serle says brusquely: "Barbara Baynton's reputation rests on half a dozen short stories, written with much ability and power, and uncompromising in their stark realism. The building up of detail, however, is at times overdone, and lacking humorous relief, the stories tend to give a distorted view of life in the back-blocks."

The 1970s advent of second-wave feminism and histories such as those of Henry Reynolds, which recorded the hitherto unacknowledged violence of European settlement, led to a reconsideration of Baynton's slender oeuvre, a recognition that perhaps her stories captured an uncomfortable truth, particularly about the lives of women, that was ignored in the preferred canon of Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson or Steele Rudd. They certainly disrupted the narrative of rural battlers that still infects Australia's myth of itself: Baynton painted a world of harsh masculine domination, of brutalised relationships and terrifying sexual violence.

Her reputation rests, as Serle noted, on a few short stories, published as Bush Studies in 1902: a series of vignettes of bush life varying from a comic description of a bush christening to the three grim tales retold here by Petty Traffickers. Baynton's realism and air of Gothic horror shows the influence of Guy de Maupassant, the French equivalent of Edgar Allan Poe. And her short narratives - especially in what is probably her best story, Squeaker's Mate - still have the power to move and shock.

Sadly, in this staging by Stewart Morrit you are more likely to notice the Victorian sentiment than the brutal power of these stories, though there are moments when these adaptations - if they are indeed adaptations - lift out of their literalness and genuinely access the horror Baynton sketched so well. Here the credit mostly lies with the committed performances rather than with the direction: this production features some fine acting from Chloe Armstrong and Margot Knight. But oh, the literalness...

The show opens with A Dreamer, an account of a young woman, newly pregnant, visiting her mother in the bush. She is not met at the station, and must make a nightmarish way through storm and darkness to her mother's house, during which she nearly drowns. I couldn't see any cuts to the story at all, although there may have been; it is narrated in its third-person entirety by the three actors who, as they speak the words, illustrate every phrase, practically every pronoun.

If a pipe dripping into a tank is mentioned, the pipe - with water gurgling through it - will magically appear against the theatre wall. If there is lightning, the lightning will dutifully flash, every time, with the proper accompaniment of thunder. If a tree must be grasped, the branches of eucalyptus will be there to be grasped. I am not sure that I have ever seen anything quite like it. That Armstrong, struggling across a bath full of water (representing the river) holding on to said branches - there were a lot of branches in this show - manages to be genuinely riveting is, on reflection, quite amazing.

Squeaker's Mate had more than one character, so at least featured a little dialogue to leaven the narration. In its pitiless description of how the useless are discarded and forgotten, this brutal story about a crippled woman reminds me of Kafka's Metamorphosis; but again, its power was muted here. While Margot Knight as the paralysed woman generates a performance of compelling physicality, it also features a performance by Joe Clements as Squeaker, the oaf who first exploits and then abandons his partner, that somehow made Baynton's picture of insensate brutalisation merely comic.

The final piece of the night, The Chosen Vessel, provides the best theatre of the night. This is a story of a woman, left alone with her baby in her isolated house, who is stalked and then raped and murdered by a passing swagman. A sequence where the terrified woman lies in the dark, as the swagman breaks a hole in the wall of her hut, is genuinely frightening: Armstrong's nervy fragility and a rather brilliant lighting design make it a scene of total suspense. Unfortunately, the structure of the story itself - it shifts perspectives from the lone, frightened woman to other characters - is not translated with any lucidity into the narrative on stage, which makes the end anti-climactic, as well as puzzling to those unfamiliar with the story.

It must be said that this show is visually rather gorgeous - Felicity Hoare's inventive lighting plays across the vast Theatreworks space, picking out with warm colours the sparse objects on Peter Mumford's set. But otherwise, it is by no means a successful transposition of prose into theatre. To be frank, it left me rather baffled: The Chosen Vessel seems to demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of theatrical storytelling. Theatre, as was thrillingly demonstrated recently in shows like Dood Paard's Titus or Barrie Kosky's The Tell-Tale Heart, is much more than moving pictures that go with words. Otherwise, why not just pick up a book?

Picture: Chloe Armstrong and Joe Clements in The Chosen Vessel. Photo: Peter Mumford