Alison's Festival Diary #1

Yes, it's that time of year again: the Melbourne International Arts Festival has invaded and transformed the city. Little Alison is like a toddler let loose in a sweet shop or a bee in a meadow blazing with flowers, rushing hither and thither in a daze of cultural greed. And what have I seen so far? Gentle reader, let me give you a taste...

Tragedia Endogonidia: BR.#04 Brussels by Romeo Castellucci. Direction/set design Romeo Castelluci, direction/vocal sound and dramatic score Claudia Castellucci, trajectories and writings Claudia Castellucci, original music Scott Gibbons. With Sonia Beltran Napoles, Claudia Castellucci, Sebastiano Castellucci, Luca Nava, Gianni Plazzi, Sergio Scarlatella, Atos Zammarchi. Societas Raffaello Sanzio, @ the Malthouse Theatre.

It is in fact very difficult to describe the impact of BR.#04 Brussels, Romeo Castellucci's astounding expression of contemporary tragedy. This is work that communicates at levels both beneath and beyond speech, and it leaves you filled with a profound wordlessness. I don't think I have seen any theatre which so radically and powerfully questions the place and meaning of language.

BR.#04 Brussels is the fourth part of a major theatre project called Tragedia Endogonidia, which was created as an evolutionary work across ten European cities. As its name suggests, Castelluci and his company are interested in exploring an organic conception of tragedy: "endogonidia" is a kind of fungal spore that reproduces by single-cell division. The tragedy explored here is far from that of the mortal, individuated hero: it is the tragedy of time itself, which erases all identity. But this anonymity, like the fungal spore, signals an immortality: individuals may die but, in its endless division, the spore persists.

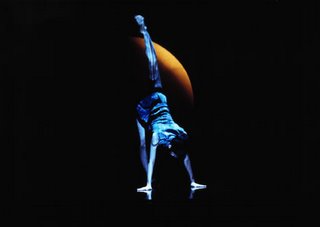

The set is simply a huge, white marble-lined cube fronted with curtains, with no features aside from six fluorescent lights suspended from the ceiling. It could be a hotel lobby, a court, a university: any institutional space. Against this sterile but human-made space, Castellucci creates a series of tableaux, punctuated by the opening and closing of the curtains, which foreground the fragility and the enslavement to time of the human body.

The "scenes" include a baby, perhaps ten months old, sitting on a blanket near the front of the space, while a robot head at the back of the stage recites letters of the alphabet; a black woman mopping the floor; an old man who enters in a bikini and then dresses in a series of layers of clothes, one over the other, transforming from a risible, feminised figure to a Rabbinic priest, thus incorporating the feminine into the priest's robes so it becomes a symbol of patriarchal authority, and lastly, into a policeman (it is notable that the uniform is that of the Victorian police). These images are at once breathtakingly simple, focusing on the sheer presence of a body in space, and richly allusive, calling up multiple historical perspectives - not only the span of a human life, from babyhood to old age, but traditions of Mosaic law, or the history of slavery.

What follows is one of the most disturbing evocations of violence I have seen on a stage. A performer dressed as a policeman undresses to his underpants and sits on the floor, next to a puddle of fake blood poured there earlier by another policeman. Then the two policemen on stage begin to beat him with their batons, accompanied by a thunderous electronic percussion: one beats him, while the other is a witness. As the victim writhes, attempting to escape the batons, he becomes covered with blood. The beating goes on longer than seems bearable: as Castellucci himself says, "time haemorrhages". It is as powerful an image of Giorgio Agamben's conception of "naked life" - mere physical being, at the mercy of the State - as I have seen. Its clear artifice only makes this image less bearable: it is as if it makes it possible to perceive the gesture wholly, without mediation.

The bloodied man is then shoved into a body bag and, in a black comment on the media's rapacity for victims, a microphone is placed near his mouth. The only audible words in this work are the prayers uttered by the man in the body bag, whose amplified sobs and gurgles are interpersed with a Hail Mary.

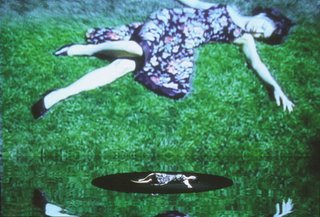

His prayers summon a kind of 19th century nightmare, as if the racial and sexual fears in the subconscious of modern man erupt on stage: a dream-sequence featuring two women, one white, one black, both in 19th century mourning dress, and an imp in a top hat with a rhino horn for a nose. It invokes common dream symbols of anxiety, such as losing hair and teeth, in a macabre series of images that almost seem like a satire on 19th century Darwinian rationality.

Finally, in an image of unparalleled poignancy, an old man sit nexts to a hospital bed, eats some bread, sighs, gets into bed, wraps the blankets around himself and vanishes before our eyes, ebbing away to leave the bed unwrinkled, as if it has never been slept in. The end of the show is signalled by a nonsensical text projected onto the curtains, like film titles.

Describing these images is, alas, inadequate to the experience of witnessing them. This is theatre of rare potency. It is possible to unwind from Castellucci's allusive theatrical images various narratives of colonisation, slavery, gender, religion, the evolution of western civilisation and the contemporary police state; but at the same time, none of these narratives - which most certainly are part of the constellations of thought around this work - go very far in explaining their power.

This is work that remains essentially mysterious, in the way that human existence is mysterious, erupting beyond mere intellect to lodge in the psyche's obscurities. Where, believe me, it takes root: I had some very strange and disturbing dreams that night. Astounding, unforgettable theatre.

1984 by George Orwell, adapted by Michael Gene Sullivan, directed by Tim Robbins. Design Richard Hoover and Sibyl Wickersheimer, lighting by Bosco Flanagan, sound David Robbins. With P. Adam Walsh, Kaythe Farley, Brian Finney, Kaili Hollister, V.J. Foster and Stephen M. Porter. State Theatre @ the Victorian Arts Centre.

The Actors' Gang is also preoccupied with the police state, bringing from Los Angeles their stage adaptation of 1984, but compared to Casthelluci's lucid, resonant images this is primitive stuff. It is easy to see why, in the current political climate, one would want to adapt George Orwell's classic portrayal of the totalitarian State: but the execution here gives the novel a didacticism that Orwell himself wisely avoided.

The conceit of Sullivan's adaptation is that Winston Smith (P Adam Walsh), an abject figure in a marked space in the middle of the stage, is undergoing interrogation after his arrest by the Party Members. During interrogation, he is forced to narrate the story of Smith's rebellion against Big Brother. As he tells of his affair with Julia (Kaili Hollister) and his attempts to join a rebel movement, his interrogaters act out the scenes, with First Party Member Brian Finney doubling as the earlier Winston Smith.

This approach is perilously close to Theatre in Education techniques, and seems to assume that that theatricality is no more than the "acting out" of stories on stage. It's difficult to see what adapting this text adds to the novel: the script remains in thrall to Orwell, and thus perhaps is particularly uninteresting - as familiar passage after familiar passage is recited by the actors - to those who are intimate with the original. Only a few scenes - for example, when Brian Finney reads from the book of the Brotherhood, which explains how total war is a means of controlling a population by destroying material excess - attain the sinister power for which it aims.

Perhaps paradoxically, given its earnest sticking to the script, this production hits another problem. Orwell's Airstrip One is so deeply English - more specifically, so deeply post-war London - that it simply does not translate into American, especially for an audience to whom American accents are not neutral. By implicitly setting the story in an imaginary US, the text loses some of the specific historical realism that gives it its potency. But more, by adapting it to a pointed critique of the Bush regime - opening with blasting pop music, for example, as a reference to the psy-op torture techniques used against suspected terrorists - it becomes didactic in a way that Orwell never was.

This is reinforced by the few textual departures from the novel, which invariably elucidate something very close to neo-con propoganda. It made me think of Alan's Moore's fierce rejection of the Wakowski brother's movie of his graphic novel V For Vendetta; Moore claimed that his story was transformed into an American-centric conflict between liberalism and neo-conservatism, abandoning the original anarchist-fascist themes. Something similar happens here: in making 1984 less specific, it also becomes less metaphorically powerful.

Like the adaptation, Tim Robbins' direction has a pedestrian and earnest quality, with the militarised mise en scene of the Party members getting old fairly quickly. And while you can't argue that the acting is not commited, it is apt to slide into mere emotiveness. It's a production that, by being earnestly faithful and unfaithful all at once, succeeds in making Orwell less than the sum of his parts.

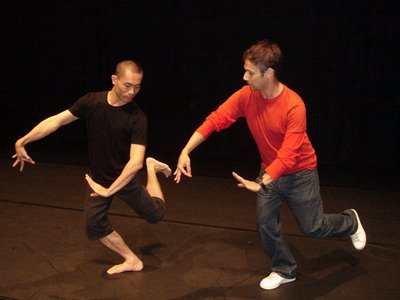

Picture: Tragedia Endogondia by Romeo Castelluci

Read More.....