Eugene Ionesco's Killing Game is notable, among other things, for probably holding the theatrical record for deaths on stage. It might even beat the record in its first scene, which starts off as an innocuous portrayal of streetlife and ends with a mysterious and deadly illness striking down everyone in sight.

Ionesco's enthusiastically comedic overkill continues through almost every scene in the play, providing every actor in his large cast with at least one death scene. But like Albert Camus in his rather more sober novel The Plague, Ionesco is concerned not so much with death itself, as with what happens to human beings in a society that perceives itself under threat: how easily human freedoms are compromised and manipulated by fear.

Written in 1974, Killing Game is one of Ionesco's later plays. Less overtly surreal than a play like Rhinoceros, it nevertheless takes Emily Dickinson's advice to "tell the truth, but tell it slant". The plague that afflicts this unnamed town kills astonishing numbers of people: 30,000 in one day. They keel over in the streets, in their homes, in prisons and hospitals, dying mere seconds after exhibiting their symptoms.

Ionesco is simply unconcerned by the realities of pathology or with the logistical details of, for example, removing 30,000 corpses a day from the streets. The literal details of what might be called his propositions about reality do not interest him.What does concern him is the absurdity of the human capacity for self-deception and folly and the possibility - always contingent - of true human communication.

Ionesco himself fiercely resisted political or ideological interpretations of his work. "The true society, the authentic human community," he wrote, "is extra-social - a wider, deeper society, that which is revealed by our common anxieties, our desires, our secret nostalgias....A work of art is the expression of an incommunicable reality that one tries to communicate".

But this doesn't mean that ideologies cannot be read in Ionesco's work. Perhaps his truest insight is the profoundly Marxist idea that society alienates human beings from themselves. "I believe that every society alienates," he said. "Even and above all a 'socialist' society...wherever one finds social functions, one finds alienation." Such refusals of the binaries of Left and Right look less wilfully eccentric now than they might have done in the 1950s, when they caused pain to critics like Kenneth Tynan, who saw them as an expression of aesthetic irresponsibility.

In Killing Game, the disease that attacks the community might be seen a metaphor for society itself. But although its black satire of a community destroying itself in order to protect itself seems grimly apposite now, Greg Stone's lively and intelligent production refuses the temptation of burdening the play with heavy-handed relevance. It speaks for itself, and so retains its complexity.

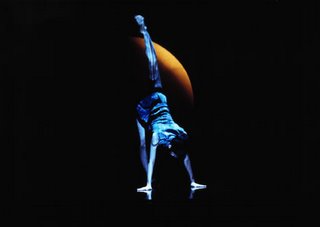

It opens as a faceless red-cloaked figure, an avatar of Death, strums a sinister solo on an electric guitar. She stands on the heights of John Bennett's striking multi-level set while the citizens of the town unknowingly go about their business below, creating a theatrical image that is very like the mediaeval idea of memento mori.

Stone's energetic student cast keeps the pace fast, exploiting Ionesco's black ironies with enthusiasm and comedic aplomb. The scenes cut from one to another across the multiple levels of the set, signalled by changes in lighting states. It's backed by an powerhouse soundtrack, including live music and a good dose of Tom Waits' The Earth Died Screaming.

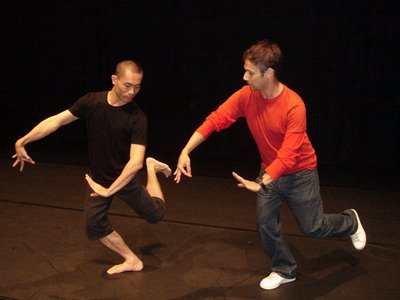

For the most part, the performances are more than creditable; the only time when their youth is a problem is in a moving (and rather crucial) dialogue between an old couple (Michael Bevitt and Helene Koen). It is not these talented young actors' fault that this scene is beyond their capacity: it is not only the physical appearance of age that is missing here, but the profound and subtle sadness with which Ionesco imbues his characters, and which can only come with age itself.

This production certainly shows off the various talents of Ballarat University's Arts Academy. And as an old Ballarat girl myself, I'm glad to say they do Ionesco proud.

Picture: Michael Bevitt and Helene Koen in Killing Game. Photo: Ponch Hawkes.